Vitagraph 6 continued from page 5

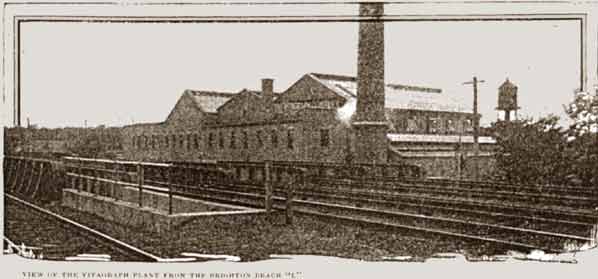

The View of the Vitagraph Village from Across the Brighton Line in 1915. The camera is on the adjacent Manhattan Beach Line right-of-way. (Picture from Motion Picture Magazine. Special thanks to Heidi Halton of George Eastman House (www.eastman.org).

Over the next five years

it would produce one-reelers of novels by Victor Hugo, Sir Walter Scott

and Bulwer-Lytton; Robert Louis Stephenson, George Eliot, Washington

Irving and James Fenimore Cooper, among others. There was Charles Dickens' A

Tale of Two Cities (1911), as well as Uncle Tom's Cabin

(1910) and Thackeray's Vanity Fair (1911), of which a reviewer

wrote: "it comes nearer to being a flawless adaptation than anything that

has appeared in moving pictures." Lest anyone think this foray into high

art had made the studio pretentious, exhibitors of the film

Elektra (1910) were told: "You have heard of

the great opera of 'Elektra.' Well, the operatic production

'has nothing on' our production. ... It is a film that will

stand 'billing like a circus.'" But there was no more certain signal that

Vitagraph was in the fray to the finish than when it rolled out the

big gun—William Shakespeare—in the form of Macbeth in April 1908, the first of eight of

the Bard's plays that were to be produced in a year's

time.

For these plays Vitagraph

already had the ideal man already in its employ, William V. Ranous, with

Barney Sherry, one of the first two actors hired for the stock company. He

had a long, if not especially notable, stage career, which included a turn

with Tomasso Salvini, the most acclaimed Othello of the 19th Century.

Ranous both acted in and directed most of these films and here the

unmemorable stage player excelled. His performance of the title role in

Macbeth, no less than his direction, won critical acclaim, even in

England, where a London motion picture weekly reviewer wrote: "This firm

are to be congratulated on the masterly way in which they have staged

Shakespeare's tragedy. The famous play contains many situations which lend

themselves admirably to effective treatment in picture form, and the

company have made the most of them."

The reality behind the

sets and costumes that drew praise was far different than the appearance.

Paul Panzer, another charter member of the Vitagraph stock company, whose

most memorable contribution to film history was as the villain in The

Perils of Pauline, recounted what went on before the cameras began grinding:

We built our own scenery and props, and we certainly must have presented an incongruous sight, doing carpenter work and painting canvas while we were dressed in the costumes of Shakespeare's time. After we had built a set we threw saw, hammer and paint brush aside and stepped on to the stage and assumed the characters drawn by the immortal Bard.

Not even Shakespeare proved a guarantor of respectability. The Chicago censor declared, "Shakespeare has a way of making gory things endurable, because there is so much of art and finish. But you can't reproduce that. The moving picture people get a bunch of Broadway loafers in New York to go through the motions and interpret Shakespeare. . . . Shakespeare is art, but it's not adapted altogether for the 5-cent style of art."

©2000 The Composing Stack Inc. All rights

reserved.

urbanography is a service mark of The Composing Stack

Inc.

Updated July 21,

2000.